Page last updated 17/2/2024.

The Student Underground - newspapers and strikes of the Vietnam era

Article

From our ubique correspondent, adapted from a piece originally intended for the University High School student audience.

0

Those of us who were around in the high school scene of Melbourne of the late 1960s and early 1970s might remember the secondary student movements of the period, initially catalysed by the movement against the war in Vietnam. During this transformative period, students distributed material and organised rallies, first to protest our country’s involvement in the war and the conscription of those too young to have voted for the government that introduced the system, then later to call for improved conditions in schools across Australia.

The looming threat of conscription awaiting students once they graduated high school was from the earliest stages a source of resentment among secondary students who remained too young to vote. This attitude was compounded by the fact that, despite the war’s relative popularity amongst the general populace for much of the 1960s, it was widely believed among radical and student circles throughout schools and universities that the war was a pointless and unjust act of imperial aggression.

Initially, university students were the most active in organising demonstrations, sit-ins and strikes. In 1968, federal Labor MP Jim Cairns, a future Deputy Prime Minister of Australia, convened a series of youth action forums to support youth involvement in political action, particularly against the war. Some of these meetings, hosted in Cairns’ own home or in venues in the inner eastern suburbs, attracted over 200 high school students. These meetings spawned several youth and student-led groups including Youth Action, Students in Dissent, and Secondary Students for Democracy.

Students became actively involved in the Moratorium anti-war marches led by Cairns. The May 1970 Moratorium march in Melbourne attracted over 100,000 attendees including large numbers of students, despite Victorian Premier Henry Bolte threatening expulsion for any school students participating.

The 1970 Melbourne Moratorium march (Bruce Postle, The Age)

Secondary students were not only active and politically aware of the pertinent political issues of the day, but also organised campaigns for student rights throughout this period. A Victorian Secondary Students Union was formed in late 1969 in response to widespread consensus on the need for an umbrella organisation and resource centre, and the VSSU came to dominate the secondary student movement in Melbourne over the following two years. From 1970 the VSSU published a tabloid-sized newspaper, Catharsis, with tens of thousands of copies of each issue distributed statewide. However, the VSSU generally avoided organising direct student action and was often accused of maintaining a passive role.

This period was characterised by student strikes, both in individual schools and in mass protests around the country. Debates in the education system were fought in schools, education departments and parliaments, around student voice, authoritarian practices at all levels of the education system, and the rights and freedoms of students. Specific demands included those related to the abolishment of corporal punishment, racism and sexism.

School protests, walkouts, and demonstrations became increasingly common in high schools by 1971. In response, the school and department establishments retaliated by suspending many students for participation in strikes and other protests, but these suspensions were usually withdrawn, sometimes after wider protests.

In April 1972, up to 1000 students, mainly from the University High School, held a strike and rally at Victorian Parliament House to protest the crisis in the education system. The success of the April action led by UHS students inspired a larger Melbourne-wide school strike in May 1972, organised by the Education Action Committee, a radical subcommittee of VSSU, following a meeting with Education Action Group students from UHS. The rally was attended by up to 3000 students during school hours, despite threats to prevent them from sitting exams. This strike led to several examples of reforms in individual schools, with Brighton High School students abolishing school uniforms and introducing a democratic school council in the aftermath.

VSSU strike (Tharunka)

Following the Melbourne strike in May 1972, student activists initiated a call for Australia’s first national school strike. The national strike was held on 20 September 1972, 47 years before the 2019 Global Climate Strikes that involved 300,000 Australians in the 20 September School Strike for Climate. The September 1972 strike received endorsement from a wide range of supporters, including the Australian Union of Students (the representative body for university students and precursor to the National Union of Students), Young Labor organisations, Resistance, the Victorian branch of the Communist Party of Australia, and many trade unions.

Students’ listed demands included

- Freedom of appearance

- Freedom of expression

- No corporal punishment

- Complete listing of all school rules

- End segregation in schools

- Increase finance for state education

- More teachers

- Equalisation of education opportunities

Some of these demands have since been achieved universally. However, it is evident that several of the same issues still remain concerns to this day.

Tens of thousands of students from hundreds of schools participated in the national strike. Many of these were actions in their individual schools, in addition to ten thousand students who demonstrated in mass protests in city centres. Following the strike, Mac.Robertson Girls’ High School students unilaterally decided to abolish school uniforms, and 40 students including the head prefect were suspended for refusing to wear uniform.

In Melbourne, up to 900 students marched from Treasury Gardens to the City Square. This attendance in Melbourne was less than in the May 1972 strike, due to a last-minute decision from VSSU to withhold support. Following the earlier strike, the majority of VSSU leadership were hesitant to endorse further demonstrations and resumed their passivity. This led to the collapse of the VSSU soon after.

The national school strike of September 1972 was the culmination of the secondary student movement that emerged first out of the Moratorium marches and anti-war movements but soon evolved to focus on the immediate questions facing schools and the education system. In the period around the national strike, individual schools across the country staged walkouts and demonstrations to advocate for reforms at school. It was in this atmosphere of heightened student political consciousness through the late 1960s and 1970s that the underground newspaper movement was born at UHS.

1

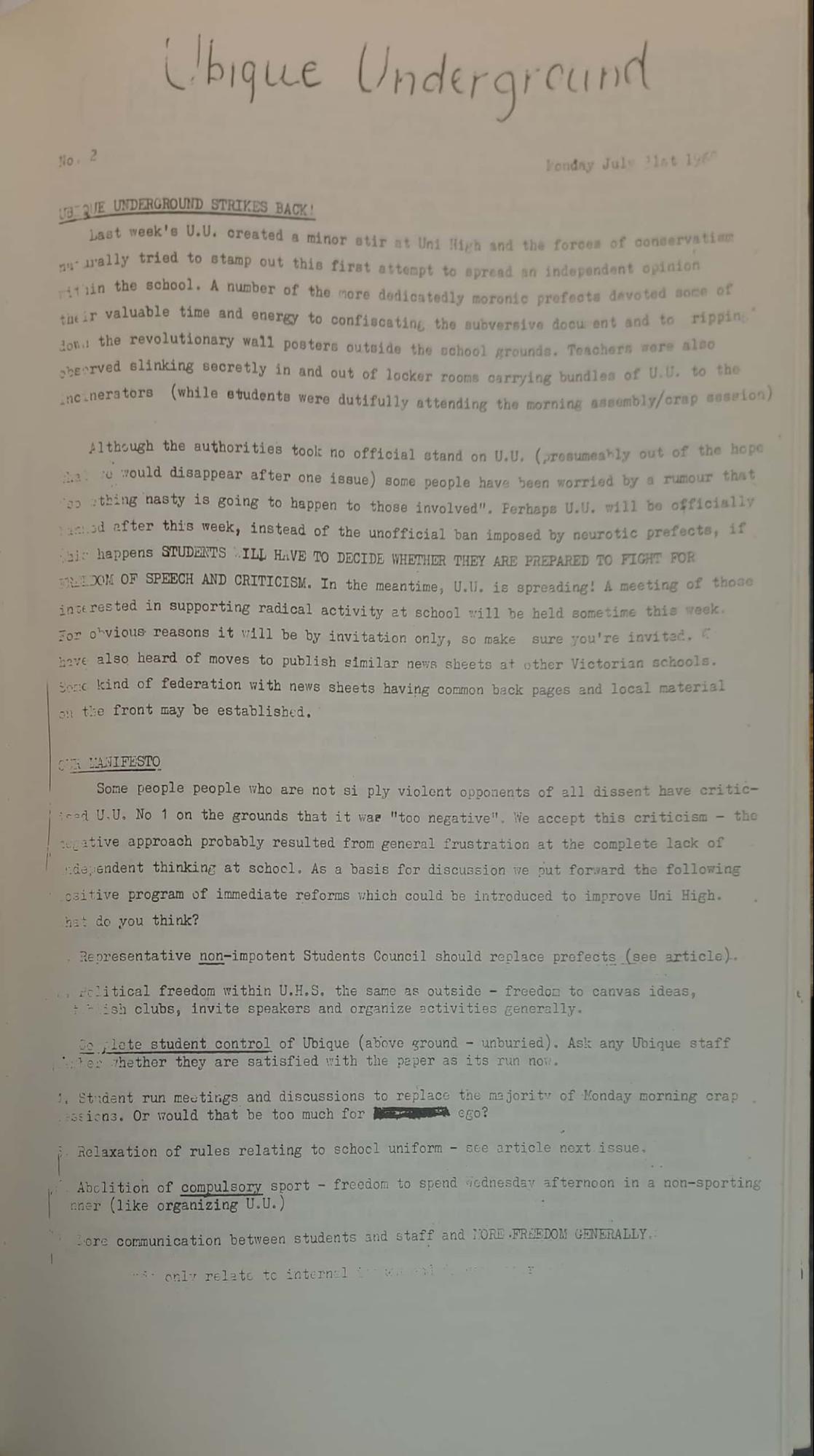

On 24 June 1968, a pamphlet was circulated among the students at the University High School. Bearing the masthead of Ubique Underground, it described itself as “a revolutionary, underground student newssheet which will attempt to heighten student consciousness of the true nature of their society”. It criticised the “above-ground” ubique as “dead but not yet buried”, attacking its content as “little more than a collection of moronic attempts at originality”.

Front page of the 2nd issue of Ubique Underground

The Ubique Underground was the earliest notable underground newspaper written by and for high school students, sparking a wave of underground newspapers that were distributed in schools around Australia. By October 1968, underground newspapers were being produced in at least 35 Melbourne schools across Melbourne, predominantly sponsored by the group Students in Dissent which had formed out of the meetings hosted by federal MP Jim Cairns. The student underground movement cooperated with other groups including university students, with many of these sheets including the Ubique Underground using a printing press in the home of a Monash Labor Club member.

The underground newspaper movement initiated by Ubique Underground spread to New South Wales, where the High School Students Against the War in Vietnam published the Student Underground. That publication was received with unprecedented demand, with 26,000 copies of the first issue of 9 September 1968 distributed to over 100 schools across the state.

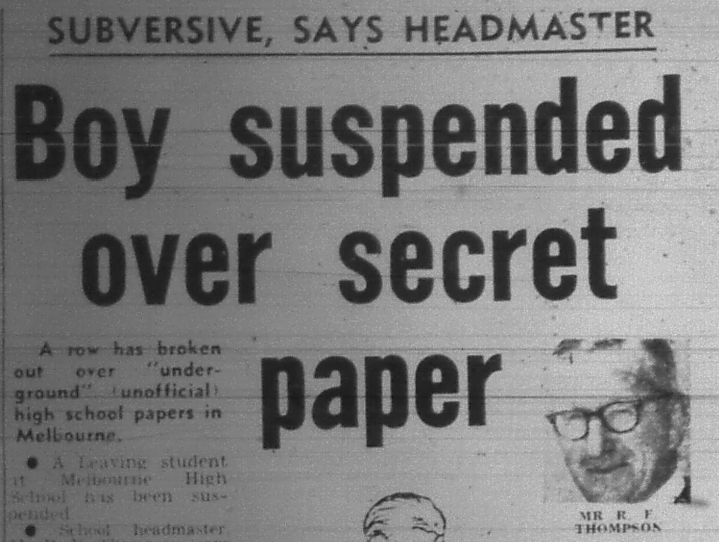

At the Melbourne High School, students published the Sentinel Underground to the great consternation of the school administration. In October 1968, seventeen-year-old student Michael Eidelson was suspended from MHS for helping to publish the Sentinel Underground. Eidelson refused to name the other students who had been editing and distributing the newspaper. The day after the suspension, two nitro-cellulose bombs were set off in the locker rooms at MHS, and a hydrogen sulphide bomb exploded in the crowded canteen at lunchtime. A Victorian MP would later suggest that “when young people are initially exposed to the mysteries of a chemistry laboratory, it is far from unusual that from time to time they will manufacture a few bombs and explode them”. A relatable experience.

The Herald headlines the Eidelson suspension

On 16 October, the Herald reported the suspension on its front page, sparking fierce debate in the media and parliament. The Liberal Victorian government and the Victorian High Schools Principals’ Association attacked the subversion of the school system and undermining of teaching staff authority. Students and teachers responded by signing petitions protesting the suspension and the repressive school system.

On 23 October 1968, the Victorian Legislative Assembly debated what the Labor Party Opposition labelled as the “considerable injustice” of the Eidelson suspension. The debate was robust; as one MP described it, “Members of this House have not had such fun for a long time”. An MP was suspended from the chamber for referring to a fellow MP as a “moral coward” and several other MPs were accused of unparliamentary language such as “You are a liar!”.

Characterising the suspension as an “arrogant exercise of authority” by an education department “appropriate to a feudal society”, Leader of the Opposition Clyde Holding challenged the Parliament: “Does Parliament believe that the function of the Education Department must be simply to educate children in reading, writing and arithmetic, and no more? Surely the function of an education system in a plural, democratic society is to train young people for the responsibilities and duties that go with citizenship.” In response, a government minister asserted that “principles of democracy, as we know them, cannot be applied to the running of a senior secondary school” and that autocracy should be the method of operation of the schools and Victorian Education Department. These questions struck at the heart of the principle of the education system, which underground papers and the student movement during the period would aim to address.

The height of Ubique Underground’s influence was evident when the following passage from an issue was read out in Parliament and characterised as “the first shots fired in the third world war”.

“Whoever heard one minute of Monday morning crap-time devoted to the question of student revolution, or the nature of capitalism … The only ‘social problems’ the illustrious Fletcher and Company would dare mention are those which do not bring into question fundamentals of our society.

We regret this subtle indoctrination of the student body. This weekly installation of bourgeois-capitalist ideas. We refuse to be trained as ‘cadres of capitalism’ moulded to fit into the slot in the capitalist system and work to perpetuate it.”

Throughout its run, the Ubique Underground and students associated with its publication and distribution were harassed and persecuted in school as “scurrilous and evil material”, with police repeatedly attempting to question students and shut down production. Despite this hostile environment, 9 editions of Ubique Underground were served to students in 1968. In late 1969, police were called into UHS and students were expelled for producing and disseminating the Ubique Underground.

Ubique Underground had a profound effect on the community and culture of UHS and schools beyond, questioning the longstanding structures and attacking the censorship of above-ground ubique. The conversations it opened paved the way for the heightened political consciousness of UHS students as they led the secondary student movement for reform and organised state and nation-wide strikes and actions. Its impact was far-reaching, inspiring similar underground newspapers in schools around the country.

The legacy of the Ubique Underground is immortalised not only in the text of the Victorian Hansard, but also in the pursuit of truth championed by a modern ubique that always vigorously and faithfully challenges and questions the systems under which we study, learn and become citizens of the future.

2

The student protest movement manifested “above ground” in the secondary student union movement, which spread throughout Australia but was “strongest” and longest lasting in Victoria. Secondary student unions formed in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia, Queensland and the ACT. The tertiary Australian Union of Students (predecessor to the NUS) at the time had an official policy to support the formation of secondary student unions. Of the unions that sprouted, only the Victorian Secondary Students Union lasted for more than a few years.

Funding was predominantly from memberships and events hosted by the VSSU (the hostile Liberal government meant government funding was out of the question although the crossbench Country Party was at least amenable to school-based student voice). Material and advisory support was provided by the Australian Union of Students and the University of Melbourne SRC, particularly use of the SRC’s office equipment such as typewriters, stencils and printers.

At its peak, VSSU membership numbered over 1000 from more than 160 schools across Victoria. The membership fee was 50c in 1970. Membership gave the right to vote at the VSSU’s weekly meetings at the University of Melbourne Union House, as well as access to discounts at many shops in the city. The VSSU also distributed its newspaper Catharsis, which was supposed to be another funding stream but often failed to be profitable, on an irregular schedule through a network of in-school distributor and city bookshops. This was a difficult task, since most members could not drive and the cost of postage was prohibitive.

The union’s activities included:

- Organising social events

- Publishing its monthly newsletter and Catharsis

- Intervening in individual suspension cases

- Organising activist events, for example learn-ins and the May 1972 Melbourne school strike

- Resource centre and information exchange

- Producing VSSU branded badges

There was also a Bill of Rights proposed, the rights including (at various times):

- Freedom of expression

- Freedom of appearance

- Student/staff control of discipline

- No corporal punishment

- Freedom of association

- End inequality in education

- No discrimination

- Democratic control of schools

- Community access to school facilities

The VSSU attributed its relatively long life, where several earlier activist groups such as Students in Dissent had folded, to its apolitical nature:

“The VSSU has always been non-political, and we believe that this is necessary if the Union is to appeal to the whole student population whatever their political beliefs.”

However, it experienced long-term internal tension between the status quo of a centralised structure effectively run by a relatively static core of cadres (“Fuehrers”) and a current for decentralisation towards each school running its own campaigns and using the VSSU primarily as a connect and resource centre. The reliance on a few active members, with limited turnover, meant that the VSSU struggled to continue when its generation of leaders graduated or otherwise became occupied. Its stance of “cooperation, not militancy”, which led it to reject endorsing the September 1972 national school strike, compounded the continuous funding challenges and recruitment issues for a largely apathetic (and where enthusiastic still practically inactive) membership, and meant that a new generation of leaders failed to immediately emerge.

So the VSSU folded.

It is not the same as a new outfit branding itself as a Victorian Secondary Students Union on social media.

Documents

- Summary of the Ubique Underground episode (Mason Johns in ubique)

- Chronology summarising Australian cases of school strikes and direct action since the early 20th century

- 25 years of secondary student revolt (published by Resistance, now part of Socialist Alliance)

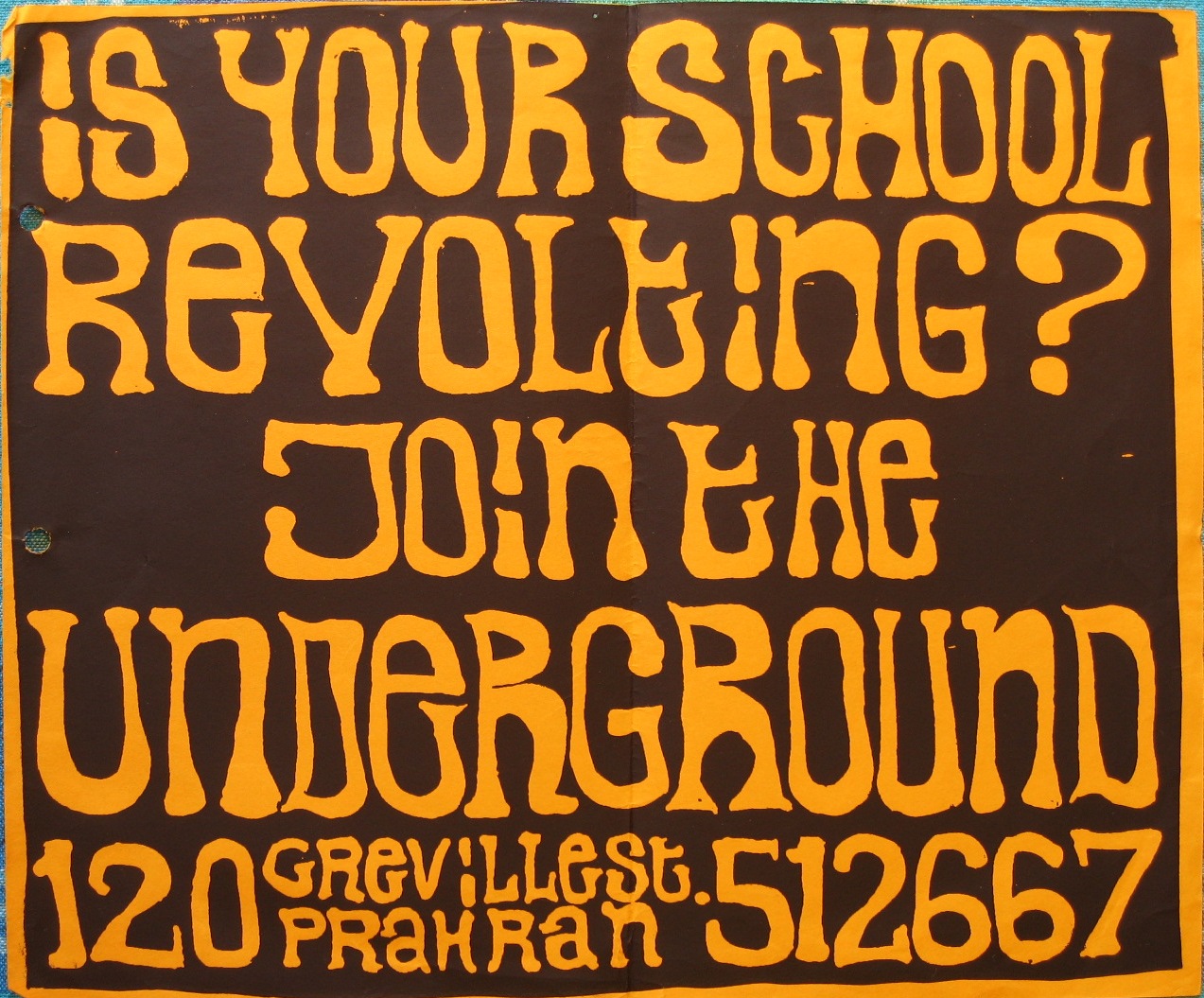

- ‘Is your school revolting?’ High-school radicalism in the Vietnam era

- I was a teenage socialist - personal recounts from Sydney including student newspapers and strikes

- The Yeast is Red - a history of the Monash University Labor Club’s off-campus headquarters, with details of student newspapers and direct action

- A History of the Democratic Socialist Party and Resistance, Volume 1 available in the State Library of Victoria - includes details of student newspapers and strikes, with critique of the Victorian Secondary Students Union

- Secondary students in dissent Student underground papers: 1968

- Students in Dissent: The Underground High School Movement 1968 (Melbourne Walking Tours, a company run by Meyer (Michael) Eidelson) - includes many contemporary newspaper clippings, both mainstream and student underground

- Victorian Hansard record of the parliamentary debate on “the failure of the Minister of Education to ensure that the exclusion of Michael Eidelson, a pupil of Melbourne High School, be lifted”, in which Ubique Underground was directly quoted

- School Power in Australia: is your child being manipulated by political operators? - a 1970 book by a New South Wales Liberal MP

Contemporary newspapers

- A Wesley student’s view of a copy of Tabloid Underground (Wesley College Chronicle)

- A secondary student’s unfavourable view of the May 1972 Melbourne school strike (Glamis Gazette, Strathmore High School student newspaper)

- Meaning of High School Strikes (Tribune, Communist Party of Australia newspaper)

- 1975 articles arguing the need for organised student voice in New South Wales and summarising some of the internal difficulties of the early Victorian Secondary Students Union (Tharunka, University of New South Wales student newspaper)

- Comments from some federal MPs on the Eidelson suspension (The Canberra Times)

- Article on a protest against Eidelson’s suspension (Tribune, Communist Party of Australia newspaper)

- Scans of some student underground newspapers

- Articles from The Age and The Herald 1968-1972 - most relate to student underground newspapers or school strikes, but also some coverage of broader education policy debates

- Hard booklet containing scans of many Melbourne student underground newspapers 1968 available in the State Library of Victoria

- Tabloid Underground (Students in Dissent)

- Ubique Underground (University High School)

- Fallout (Mentone Girls High School)

- Pravda (Peninsula High School)

- Reform (Camberwell High School and Mac.Robertson Girls’ High School)

- Treason (Highett High School)

- Folklore Underground (Caulfield High School)

- Omega (Prahran High School)

- Peon Underground (Chadstone High School)

- Sentinel Underground (Melbourne High School)

- Tirade (Croydon High School)

- Student Power (Doveton High School)